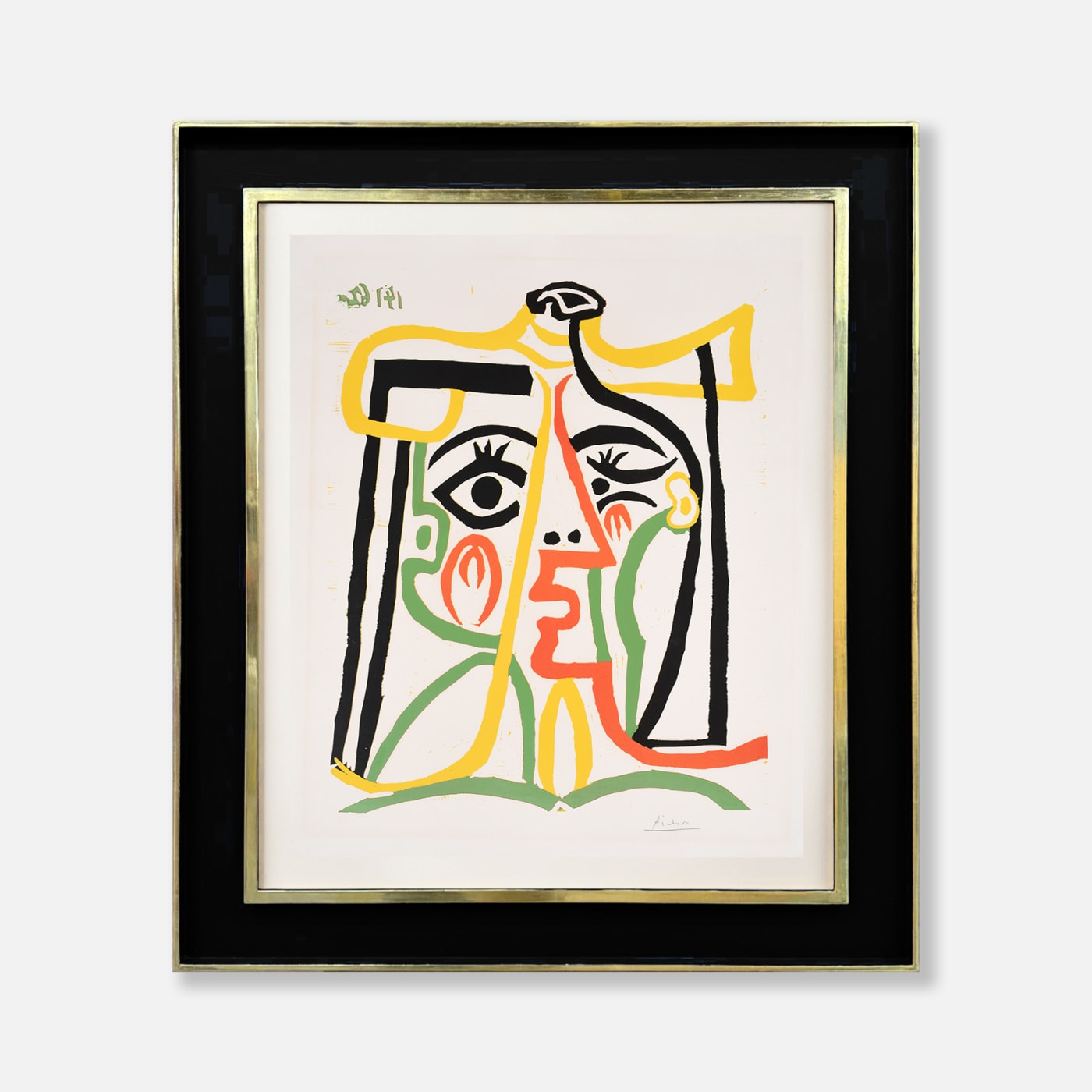

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

Collecting Guide

/

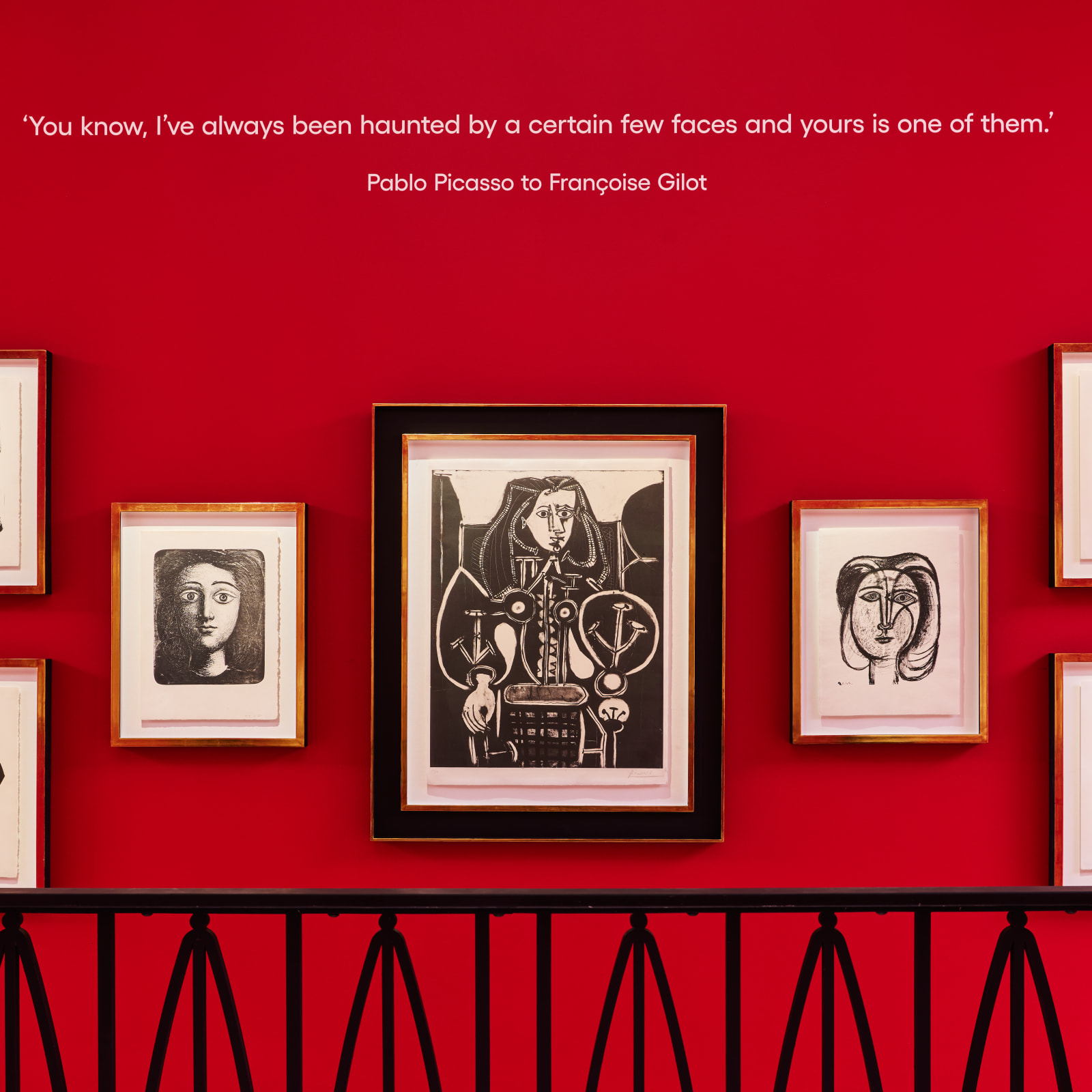

Pablo Picasso has created some of the most recognisable works in the history of art. Perennially restless in his experimentation, his artistic spirit is present throughout his range of artistic mediums. Printmaking spans Picasso’s entire career; he made his first etching in 1899 while still a teenager, and created his final print in 1972 at the age of 90.

He came to ceramics comparatively late in his career, and his ventures in this medium demonstrate the same playful curiosity and creative energy that drove his innovations in printmaking. This Collecting Guide explores the development of the artist and his techniques.

If you are interested in adding to your collection, speak to one of our art consultants now - email us at info@halcyongallery.com

ChatGPT .